Hitchens' atheist arguments under scrutiny

Regular Network Norfolk columnist James Knight dissects the popular arguments of atheist Christopher Hitchens on God, religion and faith, following on from Richard Dawkins last month, and argues that they do not stand up well to scrutiny.

Regular Network Norfolk columnist James Knight dissects the popular arguments of atheist Christopher Hitchens on God, religion and faith, following on from Richard Dawkins last month, and argues that they do not stand up well to scrutiny.

When it comes to discussions about God, I've often been baffled at how it is that Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, arguably the two most prominent atheist spokesmen in recent times, have got away with speaking so much nonsense for so long, while all the time enjoying adulation, approbation and lionisation by an ever-increasing group of followers and imitators.

So, finally getting round to it, I thought I'd go to Google-search to find what has been offered as their 'best' quotes against God, religion and faith, and show why they don't stand up to rigorous scrutiny.

As you'll see, Dawkins and Hitchens have ready-made methods for twisting meanings and distorting logic in a way that the more pliant and impressionable individuals don't seem to notice. This week I look at Hitchens.

Christopher Hitchens is a much slipperier customer than Ricard Dawkins. As you'll see from below he utters things that are so obviously true they hardly need saying (statements that just about any non-fundamentalist would agree with, theist or atheist), which thus makes them poor candidates for criticising religion. He then distorts reality to paint the kind of picture he wants, and then uses those distortions to argue in ways that everyone would agree with if his fabrications were accurate (this is another favourite trick of politicians). But it carries no more intellectual weight than if I were to get you to believe that living in Sweden comes with the same standard of living and life expectancy as living in Sudan, and then proceeded to tell you how Swedes are impoverished, desperate, repressed citizens in need of aid, investment and military intervention. You could only remain convinced for as long as I'd fooled you into thinking that Swedes have the culture, same standard of living and life expectancy as Sudanese citizens. Hitchens is good at this kind of manipulation - he must be - thousands of his admirers fall for it readily. The first case is a good example:

"Religious belief is a totalitarian belief. It is the wish to be a slave. It is the desire that there be an unalterable, unchallengeable, tyrannical authority who can convict you of thought crime while you are asleep, who can subject you - who must, indeed, subject you - to total surveillance around the clock every waking and sleeping minute of your life"

Straight away you'll notice Hitchens employs the same trick as Dawkins frequently does - in using words like 'totalitarian', 'slave', 'tyrannical' and 'crime' he appeals to terms that everyone sees as negative and undesirable, and uses them to paint a metaphor-strewn Orwellian picture of religious people being slaves to a totalitarian dictatorship. In other speeches he regularly contradicts this tenor by saying that the comfort blanket of religious belief is wish-fulfilment, so I'm not sure which he really believes.

Is religion a totalitarian dictatorship that requires our fear and dehumanisation, or is it a positive doctrine to which we might naturally gravitate for escape and comfort? What about a man under a real life dictatorship who seeks divine comfort in mental escapism - I assume Hitchens doesn't think such a man would see religion as tyrannical. Maybe Hitchens really thinks - as I suspect he does - that we each create our own interpretations of religious belief. That being the case, he offers no explanation as to why his dark 1984-esque picture of religious belief is an accurate representation of the beliefs of the highly educated religious people in the world, many of whom being more cerebral than him.

"The essential principle of totalitarianism is to make laws that are impossible to obey."11

This is not only false - in fact, if one looks at totalitarianism on earth, and if we use Hitchens' favourite example of North Korea as a prime example, then just the opposite is true - totalitarian states make laws that are easy to obey; they just involve subjection to the totalitarian leader, which means being a dehumanised slave to an ignorant, repressive, manipulative, uncaring dictator who is usually a megalomaniacal abuser of human rights and largely morally unaccountable in his thoughts and deeds.

That's a horrible life for the serf and morally ignoble for the oppressors, but there is nothing profoundly difficult about the morals - what they severely lack is the kind of profound morality and intelligent self-examination that comes from constructing a better morality that's harder to obey.

I think Christopher Hitchens would have benefitted from thinking this through a bit more; for having done so he might have been led to consider more carefully why laws that 'are impossible to obey' are that way, and what kind of metaphysical consideration they actually prompt. If the concepts of goodness, kindness, love, grace, decency, mercy and forgiveness can be conceptualised at such a grand level that they leave us hugely wanting and accountable in our pursuits of an excellence that always remains out of reach, then this should leave us more curious about concepts of divine goodness, not less curious. If such highly sought concepts of goodness, kindness, love, grace, decency, mercy and forgiveness are examples of those laws that 'are impossible to obey' they are the opposite of totalitarianism, not the 'essential principles' of it.

"Name me an ethical statement made or an action performed by a believer that could not have been made or performed by a non-believer."12

To me that is the sort of pliable question that sounds intelligent but isn't really. I think Hitchens' question shows a lack of understanding of what religious belief entails, and also the overlooking of something that should be trivially obvious. The short answer is, the question is as meaningless as asking whether quenching thirst is better than feeding oneself. It is true in most cases that there is no ‘statement’ or 'action' that a theist can make or do that others cannot, but that tells us nothing meaningful about the God debate, because a proper analysis involves much more than just the statement or action - it involves analysing the beliefs, intentions, humility, motive, and other psychological factors that do not come out in a mere action. Naturally we could name good moral actions taken by both religious and non-religious people that have produced the same results, but that does not tell us anything about what is directing the action, or whether the person is living a Godly life, and it certainly has no bearing on whether there is a God.

"On our integrity, our basic integrity, knowing right from wrong and being able to choose a right action over a wrong one, I think one must repudiate the claim that one doesn't have this moral discrimination innately, that, no, it must come only from the agency of a celestial dictatorship which one must love and simultaneously fear. Human decency is not derived from religion. It precedes it."13

Hitchens often makes this kind of argument, but it is simply an example of him continually stating the obvious and appealing to a false dichotomy to which most theists don't fall victim. No sensible believer thinks that human decency, goodness and moral thinking derives from religion - quite the contrary - it is only when we are disposed to morality that theistic interpretations of God have any power at all. That Hitchens continually makes this desperate appeal as part of his regular repertoire suggests he's trying to blind his followers with spurious appeals to the ridiculous.

"What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence."14

To express fully what is wrong with this statement would take a whole essay in itself. But briefly, it grossly caricatures religious faith to state that it is 'asserted without evidence', when, in reality, evidence is in the eye of the beholder, and different people accept and interpret different evidences differently. Maybe some people are too easily seduced by interpretations that shouldn't ever be offered as reasons for belief in God, but equally there are going to be lots of people whose psychological agitations predispose them to a scepticism that demands too much evidence, or the wrong kind of evidence.

I suspect Christopher Hitchens' main problem is that he'd never thought through properly what evidence for God actually means, and how it might be different from the more simplistic evidence found in empirical science. Never once did I ever hear Christopher Hitchens tell us what he thinks good evidence is, what makes good evidence good, how belief in God differs from knowledge of the empirical world, and what he thinks would be satisfactory evidence for God.

"Philosophy begins where religion ends, just as by analogy chemistry begins where alchemy runs out, and astronomy takes the place of astrology."15

The analogy of alchemy and astrology to their better counterparts is misjudged in relation to religion's relationship with philosophy. Philosophy doesn't begin where religion ends - religious enquiry is a key part of philosophy because the question of how we enquire is essential to what we conclude, and this is evidently true of Christopher Hitchens' anti-religion enquiries too. It appears to me that in saying "Philosophy begins where religion ends", Hitchens excuses himself from having to give the God debate a proper analysis. For a man who was so verbose on the subject, he said so few things of any profundity.

"The idea of a utopian state on earth, perhaps modelled on some heavenly ideal, is very hard to efface and has led people to commit terrible crimes in the name of the ideal."16

Indeed it has - but this is only an appeal to the most obvious of human sensibilities. Of course it is reprehensible when people commit terrible crimes to pursue some kind of dastardly personal agenda, but Hitchens knows full well that the majority of people, both believers and unbelievers, unite in finding such behaviour shameful. His point is as banal as if he had said "The idea of high street banking based on some ideal of financial institutions for our capital is very hard to efface and has led people to become bank robbers".

Does Hitchens at least acknowledge that we are trying to achieve a better world, or that it is a conceivable goal to achieve a better world? If so, then I see no reason why the most excellent principles of goodness that we can summon up need not be our main driving force in the world.

"To believe in a god is in one way to express a willingness to believe in anything"17

I don't know whether Christopher Hitchens was any good at arithmetic, but if we were to quantify the two sets (things believed in and things not believed in things), and then work out how many things there are that are believed in differently between theists and atheists, and then work out the number of things that both the theist and the atheist do not believe in, I am certain that the differences in the latter amount to a number much higher than the differences in the former.

Moreover, as I showed in my criticism of Richard Dawkins' belief-o-meter, the only God you find atheists rejecting is the kind of god (small g) that almost no sensible theist believes in anyway, so all Christopher Hitchens is saying is To believe in the kind of god I have in mind is in one way to express a willingness to believe in anything". Yes, well, given the kind of absurd caricature Hitchens creates as a god to reject, I can quite believe that people who can believe in such a god can believe in almost anything.

Final Thought

Dawkins and Hitchens repeatedly tell us why they think God does not exist with apparently witty and clever sound bites - but frankly the distortions, straw-man caricatures and poor reasoning are so clumsy that it really beggars belief that so many people hold them up as spokespeople for reason and rationality on matters of faith. Here's my rule of thumb as a starting consideration for discussing God:

The God one accepts or denies is only likely to be as intellectually tenable as the intellectual tenability of the person holding those ideas.

JK

If you want to think seriously about the existence of God - and it does require lots of serious thought - you can do much better than these two.

Click here to read the article about Richard Dawkins

James Knight is a long term contributor to the Network Norwich & Norfolk website and a local government officer based in Norwich.

The views carried here are those of the author, not of Network Norwich and Norfolk, and are intended to stimulate constructive debate between website users.

James Knight is a long term contributor to the Network Norwich & Norfolk website and a local government officer based in Norwich.

The views carried here are those of the author, not of Network Norwich and Norfolk, and are intended to stimulate constructive debate between website users.

We welcome your thoughts and comments, posted below, upon the ideas expressed here.

Click here to read our forum and comment posting guidelines

You can also contact the author direct at j.knight423@btinternet.com

11. Christopher Hitchens, God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything

12. Christopher Hitchens, The Portable Atheist

13. Christopher Hitchens, Debating Religious Belief: Debate Christopher Hitchens vs. Alister McGrath,

14. Christopher Hitchens, God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything

15.Christopher Hitchens, God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything

16. Christopher Hitchens, God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything

17. Christopher Hitchens, God is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything

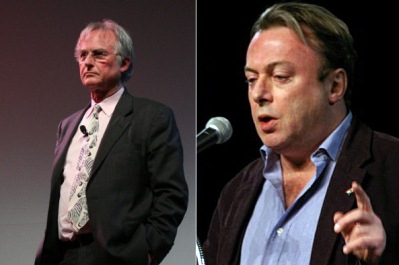

Photos: Left: Richard Dawkins by Shane Pope on Flickr (cropped) and Right: ChristopherHitchens by Jose Ramirez on Flickr (cropped)