The interaction between science and faith

Pastor Tom Chapman joins the debate on creation and evolution and offers a simple model of how science and faith interact and relate.

According to recent reports, the search for the “God Particle” is nearing its end. Some scientists are predicting that the Large Hadron Collider at CERN in Switzerland will, within a year, establish the existence of the Higgs Boson - the particle thought to account for mass and gravity. If it is found, it will confirm the validity of the “Standard Model” of quantum physics; if not found, then particle physics is back to the drawing board!

No doubt some ideologically driven atheists will argue that this is another nail in God's coffin. But in fact, the Christian faith has nothing to fear from either the existence nor the non-existence of this particle; if it exists it is simply another facet of the fascinating universe God has given us the minds to explore, and if not, it goes to show his creation is even more complex than we realised.

But we must think through how science and faith interact and relate. In our culture they are often present in opposition. And in certain respects – such as the origin and creation/evolution of life – there are of course conflicts of views. But in general there is no historical, theological or scientific reason why they should they should be seen as enemies at all, and in this article I want to give a simple model for seeing how they fit together.

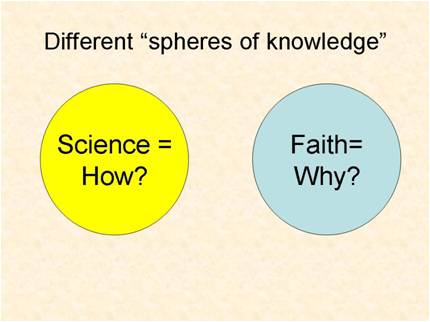

The late Stephen Jay Gould proposed that we see science and faith as two non-overlapping “magisteria” (spheres of knowledge and enquiry) dealing with distinct questions and using different methodologies. Science is interested in the “How”; faith deals with the “Why.” Science considers physical evidence using experiment and observation; faith addresses matters of ultimate meaning, spirituality and ethics, on the basis (for Christians) of revelation, history, tradition, philosophy and so on. In most cases, there is no conflict between the two because they are not relevant to each other. And some are content to leave it that way. This would include many atheists such as Gould; but it would also include many Christian scientists too who in practice make little connection between their work and their faith.

However, I am not sure this approach is entirely satisfactory from a Christian point of view, since our faith is deeply rooted in events that occur in the material world. For example, Biblical events such as the flood; miracles such as the resurrection and theological ideas such as the soul impinge on the material world which interests the scientist. It makes little difference to perhaps the majority of scientific disciplines – but if we are studying, say, astrophysics, geology or anthropology then faith and science do interact.

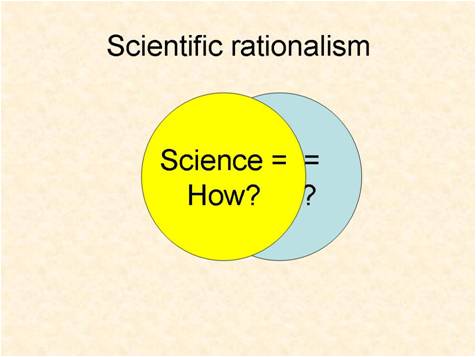

How do we resolve this? For the “Scientific Materialist” it is clear: scientific knowledge eclipses religion. Only science delivers truth; faith is in fact just a branch of psychology, and as science inevitably advances so faith will wane and die – there is no place for God. They cite the undoubted progress made in understanding the physical world in their favour and addressing practical problems as evidence, and gleefully point out the failings of “organised religion.” But of course, by its a priori assumptions, this view deliberately blinds itself to any other forms of evidence – most critically, from history. It has little to offer in realms such as morality, aesthetics or relationships as truths such goodness, beauty and love are reduced to mere evolutionary functions. It cannot account for its own origin or rationality and ignores its own historical record. “Science” is in effect a religion for many today, with its doctrines, scriptures, relics, saints, and priests to direct the zeal of the faithful.

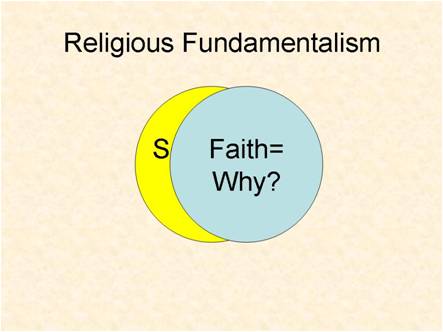

“Religious Fundamentalism” makes the opposite mistake; religious dogma eclipses the evidence. A good example of this would be Galileo's inquisitors refusing to look down his telescope and see the moons of Jupiter that would dispel their false notion of the universe. As James Knight has noted in his articles, this is still very evident today. However, we must be careful how we define “fundamentalism” as it is an easily abused boo-word. In my book a fundamentalist (in the pejorative sense) is not someone who has strong, clear beliefs in what is true, even if they fly in the face of received opinion. A fundamentalist is someone who refuses to consider or take into account any evidence that might contradict his

interpretation of what is true. In my experience, under this definition, while some creationists

are fundamentalists, others are not; they just read the biblical and scientific evidence differently. To brand them all as fundamentalist bigots is as unfair as it is to brand all who are not as liberal heretics.

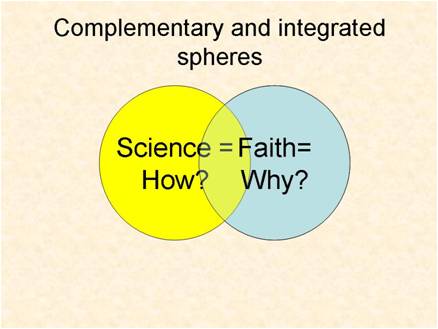

The model that works is that one of complementary, partly-overlapping magisteria. While faith and science do indeed deal with broadly distinct issues, there is a definite area of interaction between them. In this area, one may well inform or critique the other. A Christian view of the universe was the basis for the development of the whole scientific enterprise; fathers of science such as Newton, Faraday and Maxwell were inspired to understand the world around them by the doctrine of creation and God who order the universe. Likewise, a scientific view of the universe may well prompt us to at least reflect on aspects of our beliefs. As a Biblical conservative, I don’t feel free to pick and choose which passages of the Bible I will believe or ignore to suit the prevailing culture. But my

interpretation of it is certainly not infallible, and science – and other intellectual disciplines such as history or linguistics – may well send me back to my Bible in a new light.

Some people feared that the LHC would generate a black hole that would destroy the earth; this has not happened – so far, anyway! Nor will it find any subatomic particles that will do for God; there is no truth in this universe that we need to fear. High-energy clashes between Christian viewpoints are more likely to damage our cause in the long run. No need to shut the debate down; but let’s not overheat it! This causes unnecessary divisions between the confident and confusion among the vulnerable – and derision from the rest of the world. Some matters, such as the integrity of the Bible as God’s written world, are matters of first importance; but others, such as the interpretation of particular chapters of it, are not. A range of views are tenable for Christians in this matter; they cannot all be true, but they are not the touchstone of faith or integrity, and how we hold them says as much as what we hold to. All sincere Christians should surely realise that, however different our interpretation of “How” the universe came about, we are united in the “Why”; and that gives us far more in common with each other than we do with anyone else.

Tom Chapman, pictured above, is pastor of Surrey Chapel in Norwich